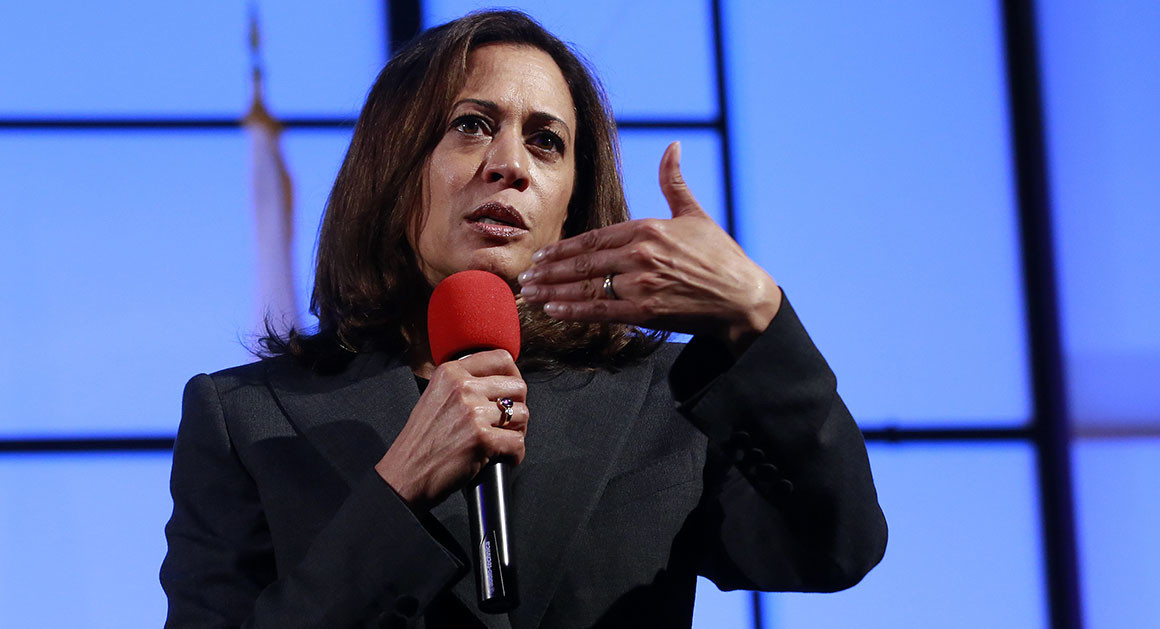

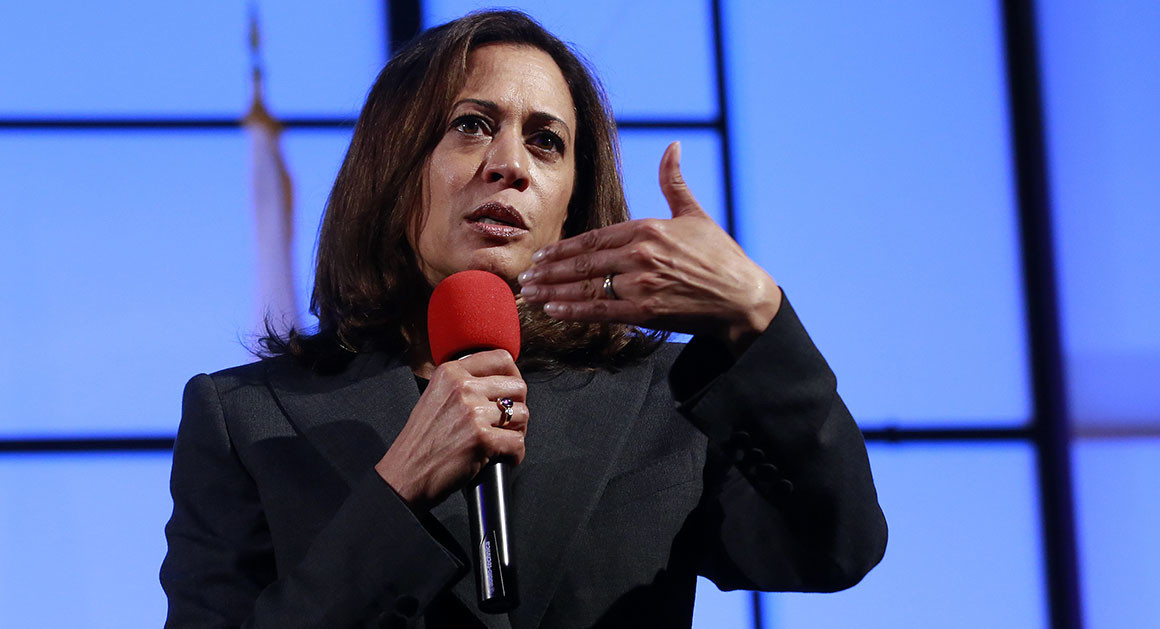

Kamala Harris’ rapid rise confounds California

Continue to article content

Harris is well regarded by most Democrats in California, according to recent polls, even if many of her supporters have been startled by her transformation from a relatively cautious state attorney general into a serious prospect for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination.

In one promising sign, her endorsement has been considered a marketable asset to California politicians in the midterm elections.

Darry Sragow, a Democratic strategist whose California Target Book handicaps races in California, says her failure to cement name recognition here is less a function of Harris’ flaws than of a geographically distant state where Washington politics “is not something that many Californians pay a lot of attention to.”

“Those numbers are perfectly OK,” he said, “particularly given that, although she may be talked about in national circles as a rising star with a great future, she has been a member of the U.S. Senate for about 16 months.”

But California voters also have a history of punishing statewide politicians who covet higher office, and Harris — who has not yet said whether she will run for president — could already be staring down its effects.

“You have to understand the way Californians view themselves to really establish a baseline as to how they view their politicians,” said Garry South, a longtime Democratic strategist in the state. “Californians have a view of themselves as living in a nation-state. … California voters have not historically been impressed when one of their state politicians decides to take a run for president. And in fact, more often than not, it has hurt that individual in California, not helped them.”

Gov. Jerry Brown’s in-state popularity took a hit when he ran for president in 1980, the second of three failed presidential campaigns. When then-Sen. Alan Cranston ran for president four years later, Cranston — though a far less charismatic figure than Harris — saw his public approval rating deteriorate. Cranston’s popularity was apparently “tarnished by his run for the presidency,” Mervin Field, then director of The California Poll, wrote at the time.

“If you’re Kamala Harris, I guess you can have visions of sugar plums dancing in your head, and more power to her,” South said. “But California voters have just not taken very kindly to their politicians running for president.”

While Harris has been busy headlining events outside the state — she recently spoke before a major fundraiser for the Michigan Democratic Party in Detroit — she’s also been careful to maintain a regular presence in California, where she drew spirited applause at town hall meetings in Sacramento and Long Beach this month.

Her advisers point to Harris’ typically low negative ratings from voters as a measure of her popularity, as does Paul Mitchell of Political Data, the voter data firm used by Republicans and Democrats in California.

Mitchell, who routinely polls the California electorate, said of Harris, “It’s real high favorables and almost no negatives among likely Democratic primary voters.”

Harris has also evolved into a more forceful politician than many Californians would recognize from her days as state attorney general, when the Los Angeles Times opined that she was often “unwilling to stake out a position on controversial issues.”

Now in the Senate and a favorite of progressives, Harris has become an outspoken advocate for protections for undocumented immigrants and “Medicare for All.” She is one of a several senators who has called for President Trump to resign over accusations of sexual harassment and assault.

“Being in the U.S. Senate has given her some sense of freedom she clearly didn’t feel when she was attorney general,” said Gale Kaufman, a Democratic political consultant in Sacramento. “She was very risk averse.”

Since going to Washington, Kaufman said, “In this world of Trump, she clearly jumped ahead of lots of people in terms of national ability to get a headline.”

Even with California moving its primary up in 2020, Harris’ growing network of political connections and yet-untested popularity in smaller, early-voting states are likely to factor more heavily than her immediate standing in California. Harris has raised more than $3 million for fellow Democratic senators this election cycle, according to her staff, including $170,000 through her email list for Doug Jones of Alabama. Following Harris’ appearance in Michigan this past weekend, she is expected to travel to New York on Friday to address the National Action Network’s annual convention.

“I don’t think her poll numbers in California are going to tell you much about how she’s going to do when the process starts,” said Robert Shrum, a longtime Democratic strategist who has worked on presidential campaigns. “I mean, look, this is a very unformed field … and trying to figure out how this is going to play out is a very difficult exercise.”

But with 2020 primary positioning already in full swing, some California Democrats are less than certain of Harris’ prospects.

“I don’t want to be negative, but I’m not aware of anything that would make Kamala’s candidacy for president viable,” said former San Francisco Supervisor Angela Alioto, who is running for San Francisco mayor in a race in which Harris has endorsed two of Alioto’s rivals.

Still, Alioto, chairwoman of Brown’s 1992 California campaign, called Harris “wonderful,” and she added, “Maybe in other states something’s happening I don’t know of.”

As for Harris’ status in California, South said, “To understand this phenomenon, you can consult the Scriptures, which say a prophet is without honor in his own country.”